Could using animals as test subjects be slowing down our scientific progress?

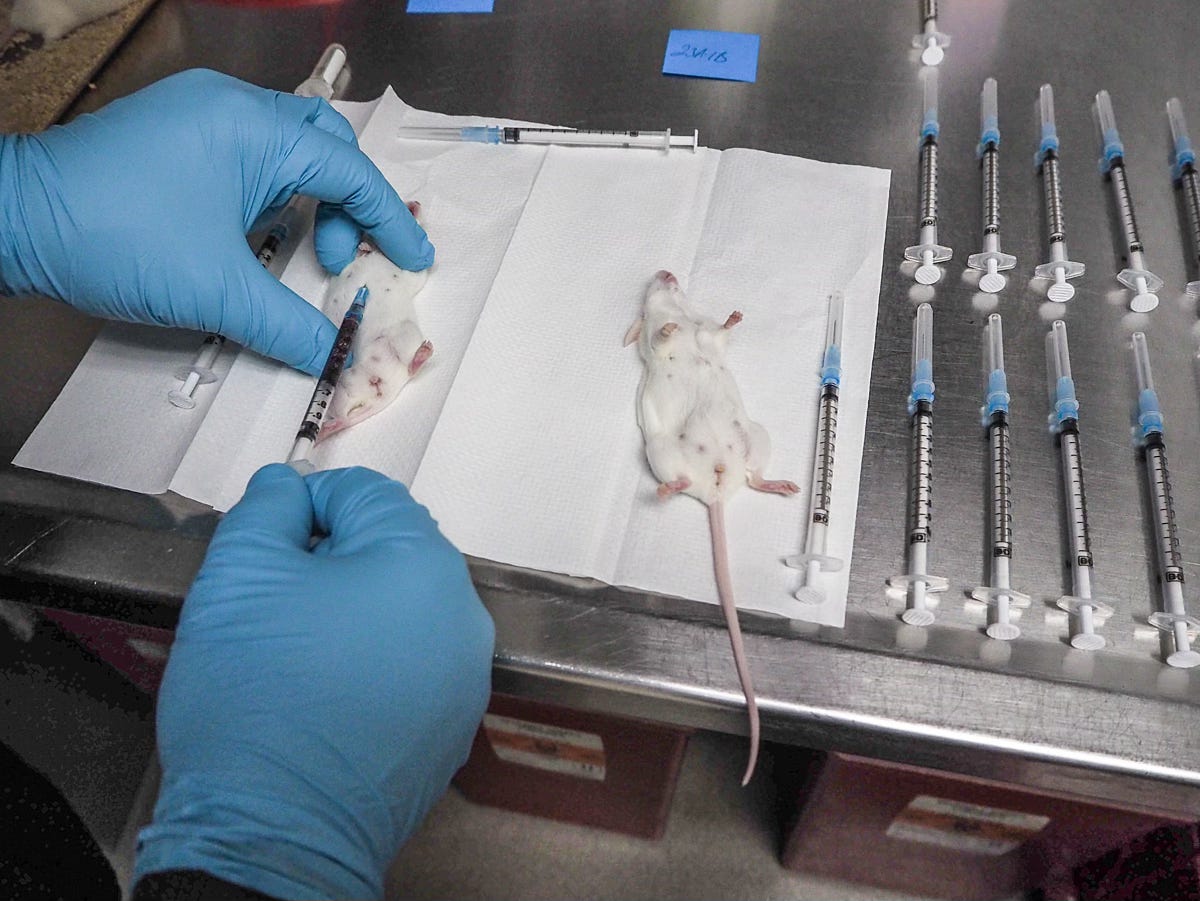

When it comes to animal experiments, the utilitarian approach is frequently mentioned. Total benefit is important and animals are used as material* for tests that may ultimately benefit humanity.

Even vegans can hardly resist testing drugs on animals for human health. When we look at it from a superficial perspective, we need animals for the drugs and treatments we owe our health to. I came across an article that questions this discourse. The article argues that using animals as test subjects prevents sufficient progress in science.

The title of the article by Karun Çekem and Mehmet Cem Kamözüt, published in the Feminist Tahayyül academic research journal, is as follows;

Overcoming False Dilemmas: Animal Experiments and Scientific Progress from the Perspective of Care

My aim in this article is to attract attention to the article and increase its readability. Because, as I said at the beginning, even vegans ignore animal exploitation in terms of health.

When it comes to animal experiments, the utilitarian approach is frequently mentioned. Total benefit is important and animals are used as material* for tests that may ultimately benefit humanity. The other approach, deontology, criticizes the utilitarian approach by arguing that animals have intrinsic value and should have basic rights. When we look at it from this perspective, the utilitarian approach remains more at the level of animal welfare, while the deontological perspective is more inclusive. However, the authors of the article say that while developing discourse in both, the subject comes to a “Trolley Problem”. This thought experiment, which squeezes either animals or humans into a narrow perspective, prevents us from seeing more inclusive possibilities.

In addition to all this, feminist animal ethics says that just as in our relationships with humans, we should also center our relationships with non-human animals on care, that is, a meticulous care aimed at competently meeting each other’s concrete needs.

The article with a feminist perspective shows that caring about animals is not an obstacle to scientific progress, on the contrary, it provides examples that caring about animals can enable the advancement of science.

Examples from the History of Science

Andreas Vesalius, who published his book on the human body in 1543, revealed the mistakes of Galenos, a known authority on the subject. Galenos, who was known for his knowledge of human anatomy, had tested many of his studies on animals. However, Vesalius had seen in his studies on humans that extending animal tests completely to humans did not yield correct results.

Then, Vesalius experienced the same limitation that Galenos experienced: the limit of being able to use the human body in scientific research. This time, Vesalius' student R. Colombo revealed that his teacher's studies were mostly on animals. For a long time, they wanted to believe that the results obtained on animals would yield the same results as on humans, and they convinced the society. This situation caused science to not progress sufficiently. Incorrect results caused time to be wasted. Perhaps if it had been done on humans, a more careful approach would have been taken and much more accurate analyses would have been made. As Donaldson and Kymlicka (2016) also pointed out, although it is clear that science would progress much faster if humans were used as test subjects, we do not see the failure to progress quickly enough as a loss because we use non-human animals.

According to the procedure, animals must be used as test subjects in some stages of the drug development process. However, as a result, the same drug must also be tested on humans. In other words, since it is tested on animals, the stage of testing on humans cannot be skipped. In addition, while scientific authorities say that testing on animals is mandatory, some health brands producing COVID -19 vaccines skipped the phases of phase-1 and phase-2, which include animal testing. And the drug was directly tested on humans and launched on the market. The statements of many authorities on the subject included the admission that animal testing is not actually mandatory. (Tezcan, 2021) Andreas Vesalius, who published his book on the human body in 1543, revealed the mistakes of Galenos, a known authority on the subject. Galenos, who was known for his knowledge of human anatomy, had tested many of his studies on animals. However, Vesalius had seen in his studies on humans that extending animal tests completely to humans did not yield correct results.

Then, Vesalius experienced the same limitation that Galenos experienced: the limit of being able to use the human body in scientific research. This time, Vesalius' student R. Colombo revealed that his teacher's studies were mostly on animals. For a long time, they wanted to believe that the results obtained on animals would yield the same results as on humans, and they convinced the society. This situation caused science to not progress sufficiently. Incorrect results caused time to be wasted. Perhaps if it had been done on humans, a more careful approach would have been taken and much more accurate analyses would have been made. As Donaldson and Kymlicka (2016) also pointed out, although it is clear that science would progress much faster if humans were used as test subjects, we do not see the failure to progress quickly enough as a loss because we use non-human animals.

According to the procedure, animals must be used as test subjects in some stages of the drug development process. However, as a result, the same drug must also be tested on humans. In other words, since it is tested on animals, the stage of testing on humans cannot be skipped. In addition, while scientific authorities say that testing on animals is mandatory, some health brands producing COVID -19 vaccines skipped the phases of phase-1 and phase-2, which include animal testing. And the drug was directly tested on humans and launched on the market. The statements of many authorities on the subject included the admission that animal testing is not actually mandatory (Tezcan, 2021).

Synthetic Alternative

Horseshoe crab blood is used to determine whether the final product to be put on the market contains pathogens that can cause disease. This species is endangered. This situation has pushed the scientific world to produce synthetic alternative substances. Countries that have made the relevant legal regulations use this substance in scientific studies. Moreover, since the production stages of the synthetic alternative can be controlled, it has become a product that provides more consistent results compared to the natural one. There is also a scientific development here. The effectiveness of the blood has been better understood, and erroneous results have been significantly reduced. If we lived in a society that respected horseshoe crabs, this scientific progress could have happened much earlier.

Science with Animals: Care as an Epistemological and Methodological Tool

When you are going to work with animals, the scientific world has a dictate to scientists: do not involve your emotions in this work. In fact, let me share a little anecdote from my own memories here: I returned to academia to do my master's degree 15 years after graduating from biology. I had been living vegan for 10 years and due to my work in the field of animal photojournalism, I had to come face to face with exploited and oppressed animals and witness their suffering many times. These experiences made me think about animal emotions and I returned to my field to delve deeper into this subject. I told a professor working in the field of zoology that the work I wanted to do should be about animal emotions and that the animals I would generally use (experiment involving observation) should be farm animals. I added that this perspective also came from my vegan life. He said to me, ‘Don’t mix your ideology with science.’

At this point, I find it useful to quote the words of the author Despret:

“ ‘Dispassionating’ knowledge does not give us a more objective world, it only gives us a world ‘without us’; therefore, ‘without them’ – the boundaries are drawn very quickly. And as long as this world is seen as a world ‘we do not care about’, it also becomes a poor world, a world of disembodied minds, mindless bodies, heartless, expectant, indifferent bodies, a world of enthusiastic automatons observing strange and mute creatures; in other words, a world that is inadequately expressed.’’

The experience of primatologist Barbara Smuts is important at this point. Smuts noticed that a baby soap that had lost her mother was still dying despite being kept warm and fed, and took her to her own bed so that she would not die alone at least. Within a few hours, the baboon miraculously came to and revived.

Another example comes to mind is Jane Goodall’s naming of the animals she observed. Goodall, who had no scientific basis, was naming chimpanzees when she was at the beginning of her studies. According to her account, her professors told her that this was wrong and that she should just give numbers. I know very well the disappointment that my approaches, which seem like such a small detail, caused to the person doing the study. Fortunately, Goodall resisted and today we know David Greybeard.

One of the good examples of studies that can be given for caring about animals: The Tree Snail Manifesto. Zoologist Michael Hadfield's work shows what it means to approach a creature much smaller than humans and much more primitive in the evolutionary process with care.

The conclusion of the article suggests that our values may be precisely what drives scientific progress. These values may encourage scientists to find more creative and reliable solutions, such as computer simulations or in vitro models.

Transforming science into something done with animals, rather than on them, and building a respectful scientific practice that is attentive to their vulnerabilities and specific needs may be a valuable touch of feminist perspective.

*In a way that seems strange to me, many articles that study animals include the animals used and their characteristics in the material section. They are approached as if they were objects.